Connecting with the land, it’s history, and aspects of myself in the White Tank Mountain Regional Park

Pool at the Bottom of Waterfall Trail

Earlier this month, I went to Maricopa County in Arizona and hiked in the White Tank Mountain Regional Park, often referred to as the crown jewel of the area due its geological and archeological history. I decided to go there following a huge rainstorm, since I read there was a waterfall trail. I went there less than 12 hours after all the rain, but already the waterfall had dried up. I realized you had to be there while it was raining or immediately afterwards to be able to see it. The ground is so parched in the desert that it sinks in or runs off very quickly. However, the pool at the bottom was filled with rainwater. The mountains got their name because they are impervious and made of granite and there are depressions at the base that fill with water. There was one giant one, location unknown, that has since disappeared after a cliff face caved in and destroyed it, however several remain in the region including this one. The pool is surrounded by the mountains, which shelter it from the wind and create a perfect mirror. It felt like a secret oasis and I loved how the reflections made it seem like the rock face continued below the horizon line. When I think of the core of my being, my intuition, and my unconscious, they are all hidden from view, and the question always arises whether I am tapping into something authentic or if it is just the fabrication of my conscious mind attempting to get it’s own way. There was something compelling too about the textures of the rock in contrast with the smoothness of the water. What we think of as empirical reality is filled with incredibly complex details, but our memories are smoother and reduced to the planes of existence that struck a deep chord with us.

Granite Mountains and Clouds, and the Suburbs of Phoenix in the Distance

Looking back from the pool towards the suburbs of Phoenix, I was struck by both how idyllic and permanent the rocks seemed to be in comparison with the ever-expanding fabrications of the hand of man. February is a beautiful time in the desert. The temperatures are reasonable and the landscape is more inviting, but each year it gets warmer and warmer during the rest of the year and storms in the monsoon season are getting worse too, or in some years they don’t happen at all. Here as elsewhere in the country, weather events are becoming more extreme. People often falsely believe that deserts are not at risk from the climate crisis, since they seem barren compared to forests and often survive on very small amounts of water. However, floods can create huge washouts, and if there isn’t enough rain that in combination with warmer temperatures impacts the plantlife, pushing species higher up the hills and making the landscape more barren.

Foothill Palo Verde trees have always fascinated me. They are so sharp-looking and thorny and their trunks are yellow-green due to the chlorophyll in their bark, which they use to produce sugar. They can survive on very little water and can live to become between 100 and 400 years old. Due to their far reaching intertwined limbs and they way they grow close to the earth, they also function as nurse plants for the saguaro cacti providing shelter until the latter are able to survive on their own. Often we think of dense vegetation as blocking light and preventing an understory from developing, but these plants have so few leaves that just enough light gets through. Nature is often much wiser than we are at figuring out how much space and protection is necessary to provide, so that symbiotic relationships can help life flourish. For the Palo Verde’s, their positive role is amplified by the nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their roots. I find their forms to be an interesting balance of grace and thorniness, chaos and order, and their ability to survive in harsh conditions is quite impressive.

It was so interesting to see this mesquite tree and then turn around and notice that the clouds emerging from behind the mountain range were forming a similar shape. Like Palo Verde plants, mesquite trees form mutually beneficial relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. They also have deep roots that lift water from the water table and distribute it through the surface layers of soil. Taken together, these two qualities enable these trees to provide food and moisture for desert life thereby increasing biodiversity. What is special about them is that they are able to endure harsh conditions and in turn help other lifeforms do the same, instead of merely competing for resources. Although they can take water away from other plants when planted near other vegetation in a yard, in the desert they don’t merely use up water they provide many benefits to the lifeforms they coexist with.

What also makes these area so special are the many petroglyphs made by Hohokam peoples who lived here until 1100 AD and, before, them desert nomads who may have roamed the area as early as 2000 BC . Some of the petroglyphs have been estimated to be up to 10,000 years old. The tanks probably held water year-round, which is what drew people to the region. These drawings marked events, functioned as ways of calling in rain or prey, and often expressed spiritual beliefs. It is beautiful to see them continuing to exist in an unspoiled way and they convey a sense of history that I found both welcome and powerful. In western society, we have developed amnesia of our past and seem to keep repeating the same mistakes. There is no doubt that life is transitory and someday even this may be erased, but as I age I recognize the importance of passing on what little knowledge I have gained and the experiences that have formed who I have become.

Saguaro are amazing in all stages of life and death. We are all familiar with their iconic presence in the desert, vertical beacons with strong arms. They can live a couple of hundred years, though strong winds can blow them down. Saguaro are known for the ability to store vast quantities of water, and many birds and creatures make their home in the holes in their arms. Even as they die, they still provide water to coyotes, carpenter ants, and other lifeforms. They are critical to the survival of desert ecosystems and now they are bellwethers for the impending collapse of the Sonoran Desert according to Yale climate scientists. If they desert collapses, these scientists argue, we are all in trouble since drylands ecosystems account for over 40% of the surface of the planet.

An article last year noted that 13 arms had fallen in the Phoenix Desert Botanical Garden that summer alone, when in previous years perhaps a single may have fallen. (https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/10/the-slow-death-of-a-desert-giant/) The life cycle of a Saguaro is extremely long: it takes a decade for two inches of growth, they don’t flower until 40-60 years old, and their first arms don’t grow until they are 70. Full maturity is achieved at 125 years. The destruction of the cacti that was observed in 2023 can be tied to the summer of 2020 when it was over 110 degrees 53 times and over 115 degrees 14 times. Sadly this happened again last year, when Phoenix hit 110 degrees or more 54 times. According to a recent article in the Washington Post, Phoenix will be one of the country’s least-habitable places by 2050, yet Phoenix is predicted to be the second hottest real estate market in 2024 ( https://www.bizjournals.com/phoenix/news/2023/11/01/uli-phoenix-market-watch-cre-2024.html). People may want to continue being lemmings by moving to cities like Miami and Phoenix, but it saddens me to think of the impact on surrounding natural areas as the climate crisis continues to worsen. The plants and animals of the Sonoran Desert were arable to adapt to the climate as it was, but these extremes will reduce biodiversity and lead to changes in what can survive here. It would indeed be sad of these cacti continue to fall and eventually disappear.

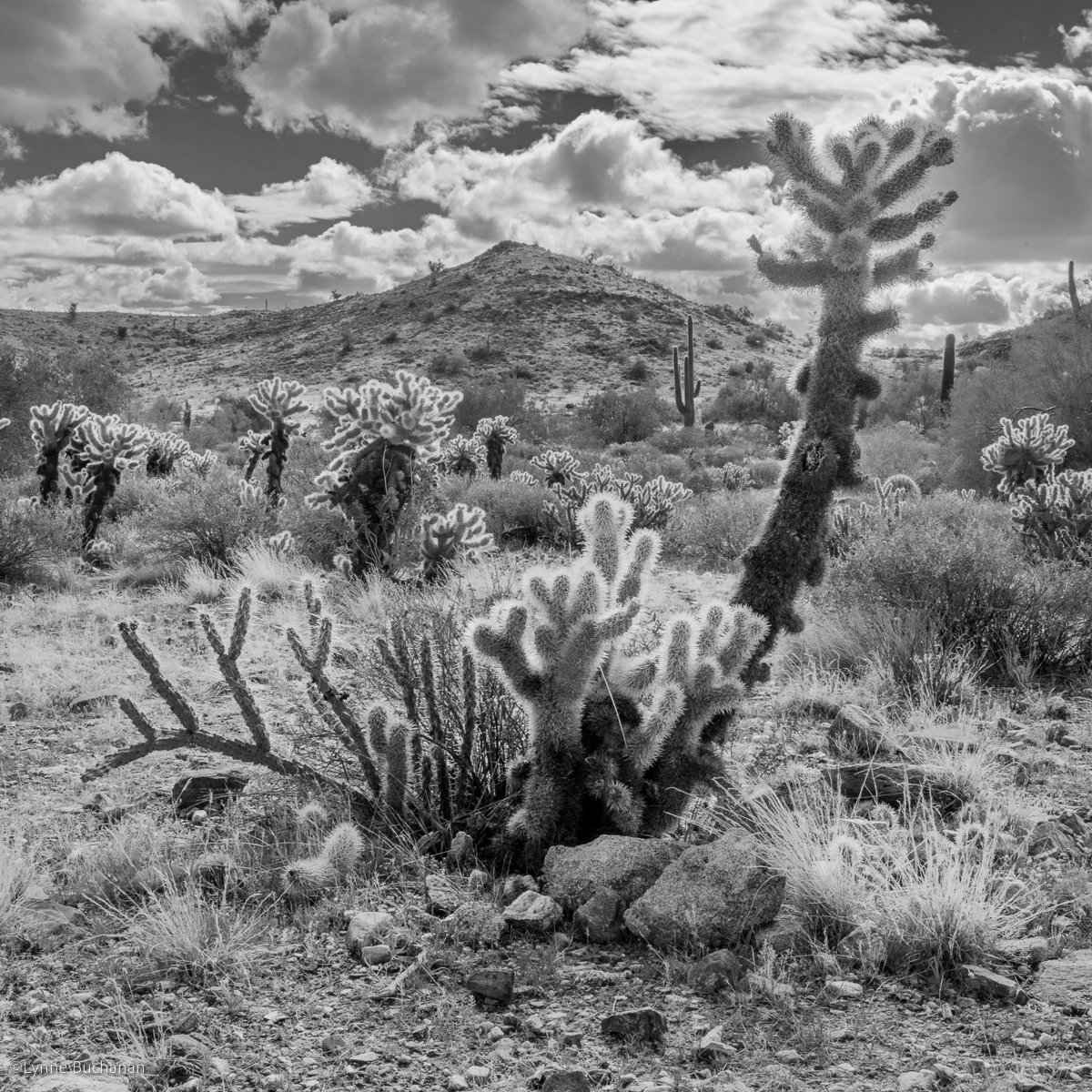

Cholla cacti are another desert favorite, and there are 28 species of cholla in the desert in Arizona. The cacti in the photo on the right are predominantly teddy bear cholla, which got their name since they deceptively look quite cuddly. They are covered with sharp spines that actually provide shade for the plants. The top silvery parts are older, while the bottom sections are dark brown. Many desert creatures depend on these cacti for food, such as birds, mule deer, bighorn sheep and javelina. The cacti are dependent on native bees for pollination, so any reductions in that population are problematic. Besides the great contributions they make to desert life, these cacti are quite beautiful.

To survive in the desert, and often in life, it is necessary to arm ourselves with protection. Yet it is also important to recognize when symbiosis and mutualism are helpful to survival and improve the quality of life. Even thorny cacti still allow other creatures to obtain water and nutrients from their bodies and birds help them pollinate in return. There are so many lessons nature can teach us about working together for the betterment of all involved. Being in the desert also reminds me of the importance of diversity and how each biosphere teaches us something different about life and ourselves.